Algae Education

We’ve collected a variety of educational resources to teach you the good and bad about algae.

Report a health concern related to a harmful algal bloom HERE or call (608) 266-1120.

If you have dogs, download this PDF to keep your dogs safe from blue-green algae.

PART 1: What are algae?

Algae are primitive, mostly aquatic, one-celled or multicellular plant-like organisms that lack true stems, roots, and leaves but usually contain chlorophyll. There are both saltwater and freshwater algae, and algae are found almost everywhere on earth.

Algae grow when they have the right conditions such as adequate nutrients (mostly phosphorus but also nitrogen), light levels, pH, temperature, etc. Usually, the amount of phosphorus available controls the amount of algae found in a freshwater lake or water body. Generally, the more nutrients found in a lake, the more algae present in the lake.

Algae are also found in streams—the slippery stuff on the rocks in the water are usually algae. Although microscopic, the “slippery stuff” is a community of diatoms, algae of various types, single-celled animals, bacteria, and fungi. This community is the favorite food of many of the stream’s herbivores.

Healthy waters need algae because algae are the primary producers in the ecosystem. They use sunlight (through photosynthesis) to produce carbohydrates and are eaten by grazers such as protozoa and zooplankton (little animals like water fleas and rotifers). The zooplankton are then eaten by small fish, which are eaten by bigger fish, and on up the food chain. A productive lake or stream produces large fish and good fishing for humans as well as supporting food and habitat for wildlife and waterfowl. In this context most algae are desirable for lakes and streams.

PART 2: What are green algae?

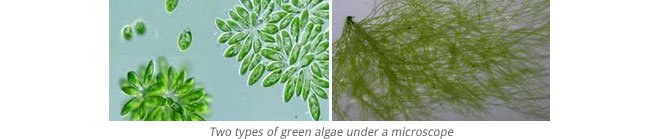

The most common type of algae is green algae. In some instances, mostly in salt water, “green” algae may also look brown, red or gold. These species can be single-celled, multi-celled or colonial. Although most are aquatic, green algae are also found on tree trunks, moist rocks, snowbanks and creatures like turtles, sloths & mollusks.

Green algae is very old; some fossils have been dated to 1 billion years. There are three classes: one marine and two freshwater. The freshwater algae are the precursors of the plants of the Earth. This is the most diverse group of algae, having some 8000 species. They vary greatly in both size and shape. However, all contain both Chlorophyll-a and Chlorophyll-b (which give them their green color), as well as secondary pigments like beta carotene and xanthophyll. Sunlight is needed for photosynthesis.

Some species feel slimy; others feel like green wool. Green algae make their own food, which is stored as starch, and reproduce by asexual reproduction. They can live up to 30 years!

Unless someone has a special sensitivity, green algae is not generally harmful to humans. However, it can reach nuisance levels, especially in the case of filamentous algae. Although there are several species of filamentous algae, all are comprised of long chains of single cells. They can form big mats that interfere with recreation, shade out sunlight, and even use up oxygen needed for fish.

PART 3: What are blue-green algae?

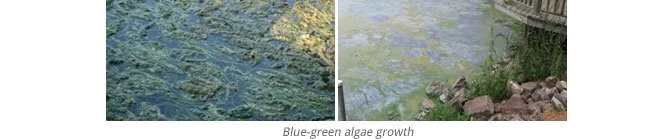

Blue-greens are very primitive organisms that are not really algae. They photosynthesize like algae, but they are actually bacteria. Scientists refer to them as “cyanobacteria” to acknowledge that they are bacteria. “Cyan” means “blue”, which refers to the fact that these organisms often appear blue-green in color. However, they can also be red, purple, blue, brown, and yellow in various shades.

The blue-greens split into two major groups: the planktonics and the mat-formers. The planktonic blue-greens are microscopic and cause the typical pea-soup green color to water. When they rise to the surface of calm or still water, they form a surface scum that tends to block the light out for other algae and aquatic plants. By shading out their competitors, blue-greens can completely dominate a body of water.

The mat-forming blue-greens form dark green or black slimy mats. These mats start growth on the bottom but eventually float to the surface where they can be quite smelly and noxious looking.

Like green algae, cyanobacteria growth is determined by conditions like adequate nutrients (mostly phosphorus but also nitrogen), light levels, pH, temperature, etc. Usually, the amount of phosphorus available controls the amount of cyanobacteria found in a freshwater lake or water body.

A dense growth of algae or cyanobacteria is called a “bloom”. Most blooms are harmless, but when the blooming organisms contain toxins, other noxious chemicals, pathogens, or other impacts to recreation or economic activities, it is known as a harmful algal bloom (HAB). Some blooms are not visible.

PART 4: Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs)

Report blooms to DNRHABS@wisconsin.gov

Need Bloom location with Lake, Town & County Name, size, duration, and photos.

Did you go swimming and start coughing a couple of hours later? Go waterskiing, jetskiing or tubing and feel a little tired? Go boating and feel nauseated? All of these symptoms could be just an everyday thing—or they could be symptoms on contact with potentially-toxic blue-green algae. Many people don’t realize they are having such a reaction because the symptoms mimic common problems.

Blue-green algae are ordinary and necessary for our lakes, streams, and rivers. However, some blue-green algae can become toxic and cause many symptoms (even death in extreme instances) to both humans and animals. Exposure can occur through skin contact, inhalation (breathing in), and/or ingestion (swallowing).

Common human symptoms caused by exposure to these bacteria are:

Skin irritations: itchy skin; red skin; blistering; hives; rash.

Respiratory Irritations: sore throat; congestion; cough; wheezing; breathing difficulty.

General body reactions such as fever, diarrhea, earache, runny nose; vomiting; abdominal pain; nausea; headache; muscle/joint pain; eye irritation; agitation.

In severe cases, convulsions/seizures; paralysis, respiratory failure, even death.

To avoid these problems, use common sense. If the water looks scummy, has a large mat of gunk, or otherwise looks iffy, avoid contact. Don’t let children or pets play in shallow, scummy areas or where algae blooms are present. Avoid jet-skiing, water-skiing, or tubing over mats of algae. Don’t use raw, untreated water for drinking, cleaning food, or washing gear. Don’t boil contaminated water, as this may release more toxins from the algae. After family members come into contact with water that may be contaminated, wash thoroughly, especially in areas covered by swimsuits (which may concentrate the algae). Thoroughly wash any clothing or fabric that has come into contact with the water. If your pet or livestock come into contact with such water, wash the coat to prevent the animal from taking potentially-toxic algae in while self-cleaning.

The State of Wisconsin has a program to track negative consequences of contacts with algae. If you think you or others (including pets) have symptoms from such contact, you should call 608-266-1120 or fill out a report on line at http://dhs.wi.gov/eh/bluegreenalgae. You will be contacted shortly by someone from the program to get details and schedule further action.

WHEN IN DOUBT, STAY OUT!

PART 5: What is being done?

Both Petenwell and Castle Rock Lakes have long been plagued with frequent blue-green algae blooms, including several that have proved toxic. Adams County has the third highest number of negative blue-green algae reports (and most are probably not reported).

Besides the health risks, the frequency and duration of these blooms (often over large areas) have also negatively affected recreational use of the lakes and the income of businesses around the lake. Wanting to do something about the lakes they love, a number of citizens, government agencies, and local businesses formed the Petenwell and Castle Rock Stewards (PACRS) in 2006-2007. This active group has prodded legislative action on funding and scientific action from a number of government agencies to start a collection of data over several years and development of a total maximum daily load (TMDL) plan for the Wisconsin River System (which includes both Petenwell and Castle Rock Lakes).

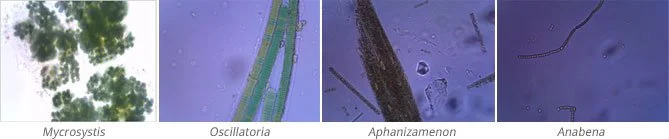

As part of this study, volunteers from the PACRS, along with Adams County Land & Water Conservation Department (Adams LWCD), UW-Stevens Point (UWSP), Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR), and National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) took water samples every two weeks from May through October for up to three years at 22 sites on Petenwell Lake and 13 sites on Castle Rock Lake. These samples were examined for the presence of five (5) algae genera known to have toxic potential. Information was posted on the NOAA Phytoplankton Monitoring Network. In addition, the WDNR took some samples that were checked for cell count using lab tests.

This series about algae in our waters was written by Lake Specialist Reesa Evans of the Adams County Land & Water Conservation Department. She is also a lake manager certified by the North American Lake Management Society.